An Interesting Measure in the Goldbergs

- On May 12, 2015

- By alzand@rice.edu

- In Musical Miscellanea

0

0

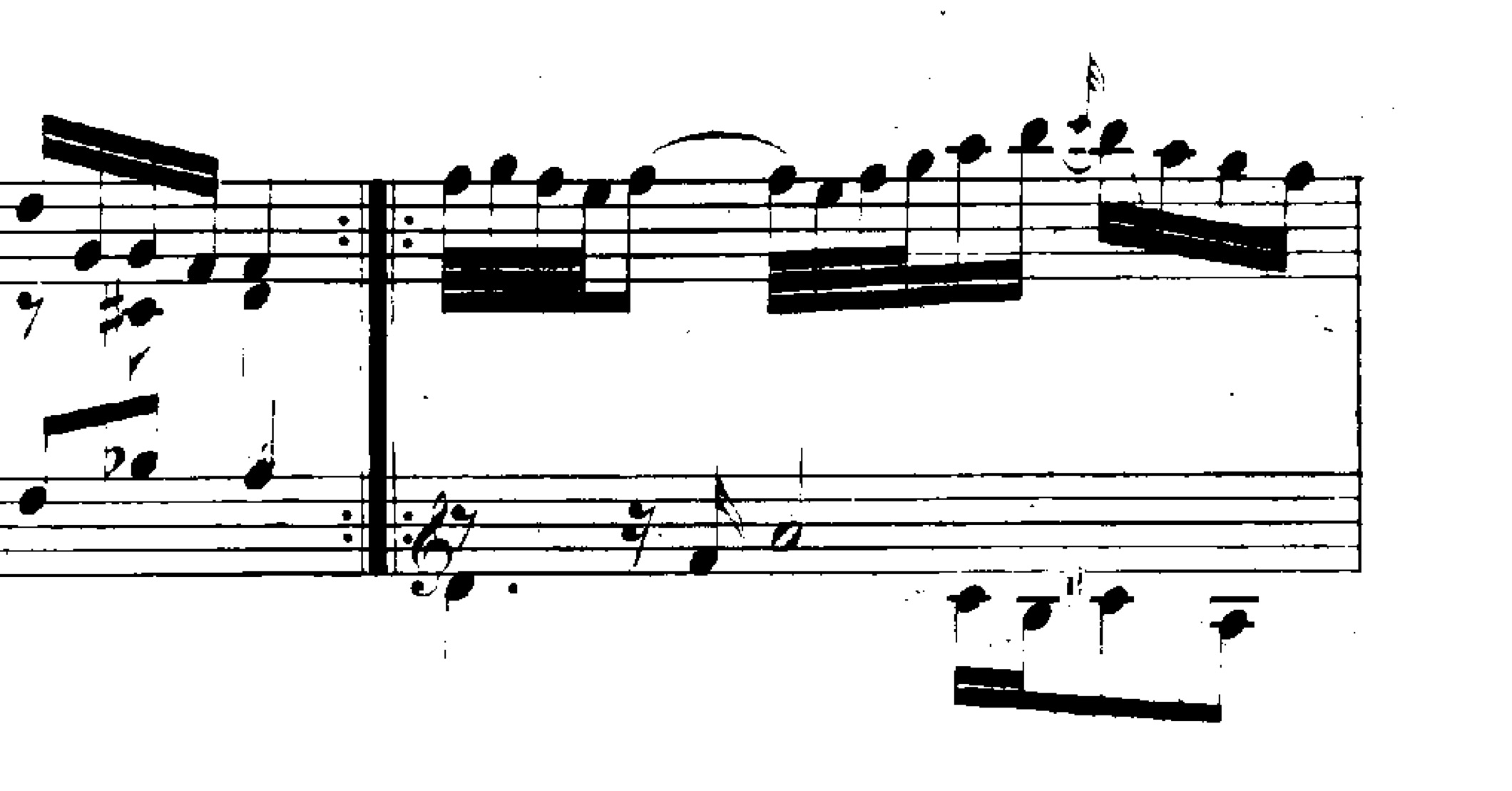

In Bach’s Goldberg Variations there’s a brief passage in variation 13 that presents some curious counterpoint. At the start of that variation’s second half (m. 17) there is what appears to be a parallel octave between the bass and the upper voice. It’s the result of an appoggiatura in the soprano—a decoration which is one of the characteristic melodic motives of the variation. Bach embellishes a repeated B (the last sixteenth of the second beat and the first sixteenth of the third beat) with an appoggiatura C. At this same moment, the bass also moves from B to C.  It doesn’t look like much on the page, but the parallelism is pretty striking and obvious in performance—nothing else is going on at that moment. I’m not sure if this measure makes it into Brahms’s Oktaven und Quinten catalogue, but it’s definitely a good candidate. It’s also an interesting example of a melodic practice Leopold Mozart rails against in Versuch einer gründlichen Violinschule. The B on the third beat is already a non-chord tone: it’s an accented upper neighbor, which resolves to the A that follows (a sixth over C in the bass). So Bach’s decorative melodic C is essentially embellishing an embellishment—decorating a non-chord-tone with a chord tone…!? Leopold Mozart tells us “this can surely never sound natural but only exaggerated and confused.”

It doesn’t look like much on the page, but the parallelism is pretty striking and obvious in performance—nothing else is going on at that moment. I’m not sure if this measure makes it into Brahms’s Oktaven und Quinten catalogue, but it’s definitely a good candidate. It’s also an interesting example of a melodic practice Leopold Mozart rails against in Versuch einer gründlichen Violinschule. The B on the third beat is already a non-chord tone: it’s an accented upper neighbor, which resolves to the A that follows (a sixth over C in the bass). So Bach’s decorative melodic C is essentially embellishing an embellishment—decorating a non-chord-tone with a chord tone…!? Leopold Mozart tells us “this can surely never sound natural but only exaggerated and confused.”

But I think this interesting contrapuntal detail reveals even more. It makes an argument for performance practice here: that this appoggiatura (and presumably all the others in this variation) must correctly be played “short.” That is, rather than being coupled to the following B to form a thirty-second-note pair, the C should be played swiftly and clipped. These two possible realizations exemplify the distinction between the long appoggiatura, which “takes its value” from the note it precedes, and the short appoggiatura, which “has no value.” The former are played on the beat, the latter before the beat. Understanding and performing this appoggiatura as short, and thus occurring before the beat, means there is no parallel here after all!

In my limited survey of Goldberg recordings, performances of variation 13—as one might expect—usually break neatly into “period performance specialists” who play the appoggiatura short (Pinnock, Leonhardt, Staier), and pianists who play it long (Gould, Sokolov, Schiff). But not always: Perahia gets it right (perhaps not surprising, given his noted musical intellect) and so does Kempff, but Landowska doesn’t.