The Leader premiere with Musiqa and Opera in the Heights

- On April 16, 2020

- By alzand@rice.edu

- In Musiqa, News

0

0

On February 23 & 29 my one-act chamber opera The Leader received its premiere on a double-bill with Anthony Brandt’s Kassandra. Presented at Lambert Hall as a co-production of Musiqa and Opera in the Heights, the work was conducted by Eiki Isomura and stage directed by Cara Consilvio. Many thanks to the terrific cast of Mark Diamond (Announcer), Lindsay Russell Bowden (Female Lover), Zachary Averyt (Male Lover), Megan Berti (Female Admirer) and Jason Zacher (Male Admirer).

The Leader is a chamber opera based on Eugène Ionesco’s Le Maître, a one-act political satire from 1953. Scored for 5 voices and large ensemble, the work is both an absurdist comedy and a timely allegory on the casual rise of despots.

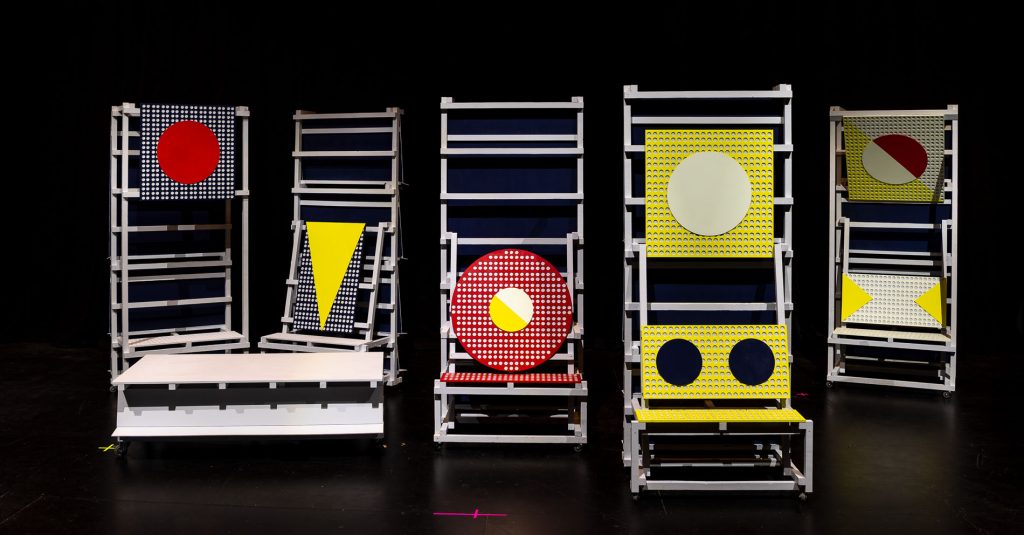

The production featured unique reversible sets specially designed by Jesús Vassallo. (below)

SYNOPSIS

The Announcer and two Admirers are chasing the Leader. Apparently he is nearby but the trio always seems to arrive a moment too late. Though he eludes them, they yearn to be in his presence. They fervently worship him from afar, following his every action with rapt attention. Meanwhile, two Lovers court each other and profess their mutual affection. Finally, the Leader approaches, the anticipation builds and the Lovers are swept up in the frenzy. The Leader is coming: his imminent arrival is hailed with increasing zeal.

On its surface, The Leader is a comedy. Its situations are farcical, its action is madcap, and its cast is full of outrageous caricatures worthy of opera buffa. The Announcer and Admirers, in their adulation, repeat the same words over and over again: platitudes and banalities echoed by mindless followers. Their behavior is preposterous, yet their unquestioning fervor seems all too familiar…

As is common in the so-called “theater of the absurd,” The Leader achieves its effect not through plot machination or character development, but through parody, a kind of exaggeration that forces us to reckon with our own sense of the world and its predicaments. It was published in 1953, six years before the playwright’s best known work, Rhinoceros, but shares with the later work its satirical tone, allegorical character and underlying political critique. Together the plays are often read as a commentary on the rise of fascism in the lead-up to World War II, and a mockery of its dangerously charismatic leaders.

But the cautionary message of Ionesco’s play is as relevant today as ever. The Leader lays bare the cult of personality which accompanies despotism. It inveighs against mob mentality and mass conformity. The cloud of uncertainty with which the play ends shows us the result of such tendencies, and serves as a rallying cry for reason and individual thinking.